The K-141 Kursk was an Oscar II–class nuclear-powered cruise-missile submarine of the Russian Northern Fleet. At 505 feet long and displacing 19,400 tons, it was one of the largest and most powerful attack submarines ever built. Designed during the Cold War to hunt U.S. carrier battle groups, Kursk carried 24 supersonic P-700 Granit anti-ship missiles (each the size of a small plane, with a ~388 mi range) and torpedoes in four 533 mm and two 650 mm tubes. Its double-hull design (a 2-inch inner pressure hull plus an outer hull of Ni–Cr steel) gave extra buoyancy and made it exceptionally survivable. Humorous details like a sauna, solarium, even an onboard aquarium reflected the crew’s efforts to boost morale during long Arctic patrols. Kursk was laid down in 1990 at the Sevmash yards in Severodvinsk, and launched and commissioned in 1994. By 2000, with the Soviet Union long gone, it was still a proud symbol of Russian naval power – the “pride of the Russian Navy” in one account – despite years of budget cuts in the Russian military.

The Final Exercises

On 11–12 August 2000, Kursk participated in a large Northern Fleet exercise in the Barents Sea alongside other ships and submarines. The exercise’s scenario pitted the Kursk against a task force including the heavy cruiser Pyotr Veliky and other fleet units. That morning, Adm. Vyacheslav Popov (Northern Fleet commander) ordered Kursk to fire two dummy (unarmed) 650 mm torpedoes at the Pyotr Veliky to simulate an attack. At 09:00, Popov gave the go-ahead; Kursk acknowledged the order. All seemed routine until 11:28 Moscow time on 12 August 2000, when sensors recorded a first explosion aboard Kursk. Just 2 minutes 15 seconds later, a second, far larger blast rocked the vessel. (These explosions registered on seismic stations and were detected as far away as Alaska, about 4.2 on the Richter scale.) The forward bow – where the torpedoes were stowed – was torn open, and Kursk lost buoyancy. By 11:31 a.m., the submarine had plunged below the surface, coming to rest on the seabed at about 350 feet (108 m) down.

Even in those first frantic moments, confusion reigned aboard the other vessels. Soviet crews initially assumed a communications failure or a benign malfunction. It was five hours after contact was lost that fleet headquarters finally ordered a search for Kursk. Two Russian rescue submersibles (AS-32 and AS-34) were dispatched, but by then it was late Sunday evening and the Barents Sea was stormy. In the chaos, offers of Western help were refused: Norway, Britain, France, Germany and others stood ready with deep-sea rescue teams, but Russian officials politely declined for nearly five days. On 13 August, Norwegian and British divers at last sailed north – too late to save Kursk’s crew.

What Sank the Kursk

From the outset, Russian admirals floated many explanations. Early official statements suggested Kursk might have hit an old mine or collided with a foreign submarine. Some even blamed a NATO sub in the area (a theory later repeated by retired Adm. Vyacheslav Popov). But subsequent investigations and recovered evidence confirmed the real culprit: a defective torpedo. Kursk had been loading a 65-76 practice torpedo (a large HTP-powered torpedo) into its 650 mm tube when an internal fault caused high-test peroxide (HTP) fuel to leak. HTP is a concentrated hydrogen peroxide mixture that powers these torpedoes, and it is highly unstable if exposed to sparks or metals. According to a government report, a tiny flaw (a faulty weld) in that torpedo’s casing let HTP spill into the tube. Once ignited, the catalytic HTP reaction triggered the first explosion – a blast equivalent to a few hundred pounds of TNT. The intense fire then detonated the warheads of the remaining torpedoes in the bow, causing a second massive explosion about two minutes later. The combined blasts ripped open compartments and tore away hull plating. Remarkably, the intervening bulkheads were so strongly built that they held back flooding of the reactors, but virtually everyone forward of the third compartment was killed instantly.

Post-accident studies by Russian experts (and independent analysts) supported this cause. A leaked Bellona Foundation report noted that the Oscar-II class carried 650 mm torpedoes with HTP fuel, and a chain reaction there could easily blow away the bulkhead between compartments. For example, one analysis showed that if just 200 kg of HTP fuel leaked and ignited, it could destroy the wall separating the first and second compartments and even breach the outer hull. In short, what sank Kursk was not external attack but a catastrophic internal malfunction of an aging torpedo. (It was later revealed that six other Oscar-II subs in the Russian fleet had similar HTP torpedoes; in the aftermath, Moscow quietly ordered all HTP torpedoes withdrawn from service.)

Voices from Below: Crew and Letter

The human toll was total: 118 officers and sailors went down with Kursk. In the dark after the blasts, however, not everyone died immediately. Investigators and family members clung to hope because 23 men – those stationed in the aft sections – managed to escape the destruction of the bow and take refuge in the ninth compartment at the stern. Aboard that small rear section, they struggled to stay alive. They sent out occasional taps on the hull and worked flashlights hoping to signal the surface. Tragically, those efforts were never heard or understood in time. Over the next many hours, they tried to use emergency oxygen and batteries, even rerouting air supplies. But without power and in freezing water, they suffocated when fire broke out in their compartment.

Decades later, a poignant piece of evidence emerged: a soaked and handwritten note found in the uniform of Lieutenant Captain Dmitri Kolesnikov, commander of the turbine section. In the dimness of the ninth compartment, he wrote a terse account of their situation (for the Navy’s eyes), then turned the page and scrawled a final message to his wife. As The Irish Times reported, his note read, “All personnel from sections six, seven and eight have moved to section nine. There are 23 of us here… We have made this decision because none of us can escape.”. The note was written between 1:34 and 3:15 pm (roughly two hours after the explosion) while he waited in darkness, aware that rescue was unlikely. Kolesnikov’s wife Olga, shown on TV later to be barely able to speak, said she had “a feeling that he was alive” and that now, at least, “I see that there was a reason for this pain.”. In all, 115 bodies were eventually recovered when Kursk was raised; the remains of Kolesnikov and two others were identified. (Only four bodies were ever pulled out through the escape hatch by divers.)

Rescue Efforts and International Response

The rescue attempts themselves became a harrowing saga. Immediately after the accident, three Russian mini-submarines (rescue bells) were dispatched to try to reach Kursk’s hatches. In rough weather, each time they failed to latch onto the escape hatch at the stern. Hours dragged on with no communication. Meanwhile, the Navy’s emergency buoy – a device meant to float free and mark the location – had been turned off on a previous patrol, delaying the initial search. When foreign rescue teams arrived around 15–17 August, Norwegian divers worked at last to dock a British LR5 submersible to the hatch. They pried it open just 10 days after the disaster, only to find the compartment flooded and the men deceased.

In Russia, public frustration boiled over. The bereaved families flocked to Vidyayevo naval base, demanding answers. Wives and mothers accused the government of indifference. “Putin has got nothing to say to us,” said Yekaterina Bagryantseva, widow of a senior officer. “I don’t believe they’re dead,” sobbed Irina Belozorova, another widow, believing her husband might still be alive deep below. In Murmansk crowds, one angry woman screamed to Defense Minister Ilya Klebanov that senior officers should “take off their epaulettes” for the delay. Some relatives even refused to join the national day of mourning declared by President Putin, solemnly saying they would only truly grieve once their loved ones’ bodies had been raised.

Western nations watched closely. President Clinton himself offered condolences and American rescue help. In a phone call, he told Putin, “My heart went out to the people at the bottom of the sea”. Putin replied that he faced “no good option” – he had chosen not to rush in for fear of making things worse. (In later interviews he admitted privately that a 2-meter gash had flooded the first three compartments and likely killed the crew within a minute or two.) Eventually, under intense pressure, President Putin authorized British and Norwegian teams to join the rescue on the fifth day. A Navy Times summary noted that “the disoriented Russian navy command wasted hours... turned down offers of Western assistance” and only after a week “invited Norwegian divers,” who opened the hatch too late. According to investigators, all trapped sailors had perished by about 8 pm on 12 August – only eight hours after the explosions – likely from carbon monoxide poisoning in the dark, oxygen-starved compartment.

Putin and the Political Fallout

President Vladimir Putin’s handling of Kursk became a political flashpoint. At the time, Putin was vacationing in Sochi and did not immediately return to Murmansk. State TV cameras later showed the somber president walking among grieving families, but by then the damage was done. Families accused him of callousness. Irina Belozorova told him, “I’ll tell him how glad I am that I didn’t vote for him. He’s not a president. He’s just a stooge.”. Vice-Admiral Vladimir Dobroskuchenko, attending a family memorial, simply declared: “We grieve that such a tragedy happened. The best monument for them is for us never to forget them.”. In a rare act of contrition, Putin later said he felt “a great feeling of responsibility and guilt” for the disaster, and on CNN famously replied “It sank” when asked about Kursk. In private, he told Clinton that the disaster “didn’t affect my standing” in the polls – an admission that even his own pollster found hard to justify. (Indeed, later data show his public approval dipped briefly but then recovered.)

Internationally, Kursk also became propaganda fodder. Russian officials toyed with conspiracy theories (a NATO sub collision) and blamed an outdated Soviet-era beacon system for the delay. Western analysts were unconvinced. Journalist Seymour Hersh later reported that U.S. submarines were monitoring the exercise but denied any contact. The U.S. and allies pointed out that modern Western torpedoes had long since abandoned volatile HTP fuel due to safety issues.

Salvage of the Russian Submarine Kursk

In August 2000 the Soviet Oscar‑class submarine K-141 Kursk exploded and sank in the Barents Sea at a depth of about 108 m (354 ft), killing all 118 sailors aboard. Fifteen months later, in May 2001, Russia awarded a salvage contract to a Dutch-led team. A Mammoet–SMIT International joint venture (50/50 Mammoet and Smit International) was formed to recover the wreck. Mammoet – a heavy‑lifting specialist – led the engineering of a custom lifting system, while Smit handled marine operations (deploying vessels, anchors and divers) and converted a 130 m semi‑submersible barge (the Giant 4) as the lifting platform. Because the bow section was shattered (with unexploded torpedoes aboard) and unstable, the plan was to cut off and leave the damaged bow on the seabed before lifting the rest.

Key dates: Kursk sank on 12 Aug 2000. The Mammoet–SMIT team contracted for salvage in May 2001. Over the summer of 2001 they designed and built over 3,000 t of custom equipment (special cutting and lifting gear) and modified the Giant 4 barge. By August 2001 the barge and equipment were on site in Norway. Throughout Sept 2001, divers cut holes in the hull and severed the bow. The main Kursk hull was lifted on 8 Oct 2001 (an 11‑hour operation), and by late October it was towed into Murmansk for final inspection. The severed bow (with torpedoes) was intentionally left on the seabed to be dealt with later.

Lifting System Design (Giant 4 and Strand Jacks)

The Giant 4 barge was specially adapted to carry the Kursk underneath its hull. A large rectangular opening and massive cradles were built into Giant 4 so that the Kursk’s hull (sail and tail) would fit up into the deck rather than sit on top. In other words, when lifted, the Kursk would be suspended below the barge in these saddles – its conning tower and fins fitting into notches – not placed on the barge’s deck. (This corrects early misconceptions that the sub was “mounted” on the barge; in fact it hung beneath it.)

The lifting equipment consisted of 26 hydraulic “strand” jacks mounted on Giant 4. Each strand jack was a vertical, computer‑controlled piston capable of pulling 900 tons, gripping a bundle of high‑strength steel wires. In practice each jack reeled in its cable a few inches at a time, all jacks synchronized by computer to keep the lift level. In calm seas the system could work in unison; in rough weather each jack frame could slide vertically to compensate for up-and-down motion. In total the strand‑jack system could lift over 23,000 tons (well above the Kursk’s weight), though about 9,000 tons of force was actually required to overcome the hull’s suction in the mud. The system also had heave‑compensators to steady the cables through waves (up to ~8 ft of swell).

Cutting Off the Bow Section

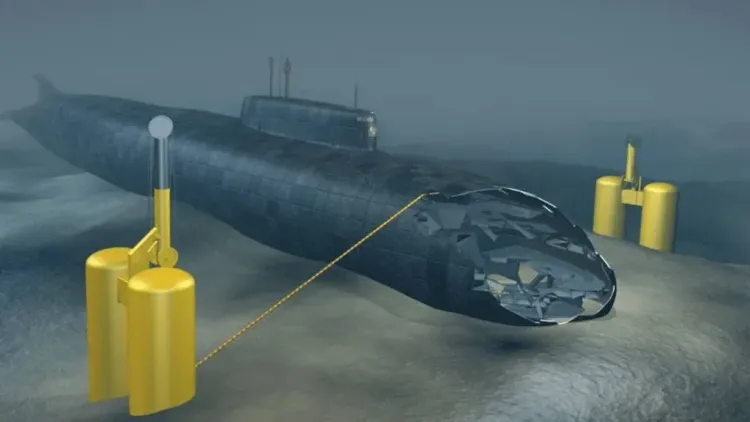

The Kursk’s forward torpedo compartments had been blown apart by the explosions and posed a safety risk, so Mammoet-SMIT removed them before lifting. Divers first placed two large suction anchors into the seabed, one on each side of the wreck. A specialized cutting wire (a steel cable with abrasive buffer) was strung between these anchors. Hydraulic cylinders on top of the anchors then pulled the wire saw back and forth through the hull, much like a giant submerged jigsaw. This robotic wire‑saw system carefully cut through the double hull and internal bulkheads of the bow section. (The saw had to be operated with extreme caution due to the risk of sparks igniting any residual torpedo fuels.)

Concurrently, the team prepared the main hull for lift. Using high-pressure water jets (with sand abrasive), divers drilled 26 large holes (about 2.3 m diameter) through both the outer and inner hull skins. Through these holes they inserted 26 gripper plugs (like giant toggle bolts) that would anchor on the inside of the pressure hull. Once opened, each plug acted as a strong seat for a lifting cable. Over several days in late summer 2001 the saw wire completed its cut, severing the damaged bow section from the rest of the submarine. The bow (with its torpedoes) was left on the seabed to be dealt with later.

Attaching Cables and the Lift

After the bow was cut away, each of the 26 cables was threaded through the hull holes and secured to its plug. Computer control ensured all plugs (and their attached strand‑jack cables) were properly aligned. Only when every gripper was in place could the lift begin. At 03:45 on 8 October 2001, all 26 strand jacks started pulling in unison. The jacks climbed inch by inch, lifting the Kursk straight up off the seafloor. Roughly 11 hours later (around 15:00) the entire hull broke free of the mud’s suction. (Interestingly, divers reported that Kursk was not as deeply embedded as feared, so “almost no suction” remained as it rose.) Throughout the lift, remote cameras and divers inspected the cables and hull; an independent radiological team confirmed that the intact reactor compartments showed no radiation leaks.

At the end of the lift, the Kursk was locked into position under the Giant 4. Its sail and tail fins settled into the specially cut recesses in the barge, firmly held by the 26 clamped plugs and saddles. Notably, the submarine was suspended below the barge – the Deck of Giant 4 simply spanned over its hull – rather than being carried on top. In fact, eyewitness reports describe Giant 4 pulling up its anchors and drifting slightly to level out, all while carrying the Kursk hanging below.

Towage and Crew Recovery

With Kursk under its belly, Giant 4 was towed to port. On 10 October it arrived off Roslyakovo near Murmansk, Russia. The Navy had prepared a shallow dry dock that was too low to accept the barge-sub combination directly. So Russian engineers attached buoyant pontoons to lift the entire assembly up about 6 m. Once the hull cleared the water, the pontoons and barge were guided into the dock. In a special enclosed dock facility, the 26 plugs were released and the submarine carefully pulled out of Giant 4.

That facility then became a forensic hangar. Investigators and medical teams entered the submarine’s remaining compartments to recover the sailors’ bodies and examine the wreck. (British divers had already entered the stern the previous year and recovered 12 bodies along with Captain Kolesnikov’s note, but the final tally of retrieved remains was 115 of the 118 men.) The crews of Mammoet–SMIT, the Russian Navy and allied divers fulfilled the mission: all recovered remains were returned to Russia for burial, and the two nuclear reactors were confirmed safe and intact.

In sum, the Kursk salvage was a remarkable engineering feat. In just five months Mammoet–SMIT custom‑designed complex cutting gear and a powerful jacking system and accomplished the world’s deepest recovery of such a heavy object. The operation cleared the wreck from sensitive waters, retrieved the lost sailors’ remains, and fulfilled the promise to bring Kursk home.

Aftermath: Reform and Remembrance

The Kursk disaster had long-term consequences for Russia’s navy and its public memory. Within weeks, the Navy quietly removed HTP-fueled torpedoes from service, acknowledging their danger. Officials reshuffled personnel: Northern Fleet commander Admiral Popov (blamed for the slow response) was replaced, and Deputy PM Ilya Klebanov took charge of the investigation. However, few top leaders were punished. The government did publish a 133-volume inquiry, though only a four-page summary was released publicly.

Kursk lives on in Russian collective memory. Memorials and annual ceremonies mark the loss of the “118 brave sons,” as one plaque puts it. In August each year, wreaths are cast in the sea at the sinking site and services held in sailors’ home ports. Some relatives and dissidents view Kursk as a symbol of official failure. In 2012, a Saint Petersburg protest featured a placard reading “Kursk – They Drowned in Silence”, reflecting lingering anger about the cover-ups and delays. Meanwhile, chroniclers and filmmakers continue to revisit the story (e.g. documentaries like “Kursk: 10 Days That Shaped Putin”). In Russia today, the disaster is often cited as a lesson in military accountability and the hazards of old technology. Vice-Admiral Dobroskuchenko’s words – to never forget Kursk’s tragedy – encapsulate its legacy as both a national wound and a cautionary tale on the perils of pride.

Sources: Detailed accounts of Kursk’s design, sinking and aftermath have been documented in news archives, official transcripts and investigative reports. Contemporary quotes come from interviews with victims’ families, Russian officials and foreign leaders. Much of the technical and historical information is compiled from retrospective analyses by defense experts and media, and all factual claims are supported by those sources.